GHOST DANCE ,LA GHOST DANCE ENGLISH ET FRANCAIS

Ghost Dance

The Ghost Dance (Caddo: Nanissáanah, also called the Ghost Dance of 1890) was a new religious movement incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. According to the prophet Jack Wilson (Wovoka)'s teachings, proper practice of the dance would reunite the living with the spirits of the dead and bring peace, prosperity, and unity to native peoples throughout the region. The basis for the Ghost Dance, the circle dance, is a traditional ritual which has been used by many Native Americans since prehistoric times, but this new form was first practiced among the Nevada Paiute in 1889. The practice swept throughout much of the Western United States, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As the Ghost Dance spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs. This process often created change in both the society that integrated it, and in the ritual itself.

The chief figure in the movement was the prophet of peace, Jack Wilson, known as Wovoka among the Paiute. He prophesied a peaceful end to white expansion while preaching goals of clean living, an honest life, and cross-cultural cooperation by Native Americans. Practice of the Ghost Dance movement was believed to have contributed to Lakota resistance. In the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, U.S. Army forces killed at least 153 Miniconjou and Hunkpapa Lakota people. The Sioux variation on the Ghost Dance tended towards millenarianism, an innovation that distinguished the Sioux interpretation from Jack Wilson's original teachings. The Caddo Nation still practices the Ghost Dance today.

Paiute influence

The Northern Paiutes living in Mason Valley, in what is now the U.S. state of Nevada, were known collectively as the Tövusi-dökadö (Tövusi-: "Cyperus bulb" and dökadö: "eaters") at the time of European-American settlement. The Northern Paiute community thrived upon a subsistence pattern of foraging and augmenting their diets with fish, pine nuts, wild game, and foraging for roots such as Cyperus esculentus.

The Tövusi-dökadö lacked any permanent political organization or officials. They followed self-proclaimed spiritually blessed individuals who organized events or activities for the betterment of the group as a whole. Community events centered on the observance of a ritual at a prescribed time of year or were intended to organize activities like harvests or hunting parties. In 1869, Hawthorne Wodziwob, a Paiute man, organized a series of community dances to announce his vision. He spoke of a journey to the land of the dead and of promises made to him by the souls of the recently deceased. They promised to return to their loved ones within a period of three to four years.

Wodziwob's peers accepted this vision, likely due to his reputable status as a healer, as he urged the populace to dance the common circle dance as was customary during a time of celebration. He continued preaching this message for three years with the help of a local "weather doctor" named Tavibo, father of Jack Wilson.

Prior to Wodziwob's religious movement, a devastating typhoid epidemic struck in 1867. This and other European diseases killed approximately one-tenth of the total population, resulting in widespread psychological and emotional trauma. The disruption brought disorder to the economic system and society. Many families were prevented from continuing their nomadic lifestyle. Left with few options, many families ended up in Virginia City seeking employment for wages.

Round dance influence

Referred to as the "round dance", this ritual form characteristically includes a circular community dance held around an individual who leads the ceremony. It was used in many community rituals. Often accompanying the ritual are intermissions of trance, exhortations and prophesying.

The anthropologist Leslie Spier used the term "prophet dances" to describe this kind of ritual during his studies of the Pacific Northwest tribes. He studied peoples of the Columbia plateau (a region includingWashington, Oregon, Idaho, and parts of western Montana). As Spier's study was conducted at a time when most of these rituals had already incorporated Christian elements, investigation of the round dance's origin was complicated.

Enculturation and diffusion are not the only explanations for the common circle dance rituals. Anthropologist James Mooney was one of the first to study the circle dance. He observed striking similarities in many Native American rituals. However, he also claimed that "a hope and longing common to all humanity, manifests through behavior rooted in human physiology and common experience", therefore alluding to either the notion of universal imprints on the human mind or to ubiquitous behaviors drawn from universal life courses that led to the ritual form.

The Prophet

Jack Wilson, the prophet formerly known as Wovoka, was believed to have had a vision during a solar eclipse on January 1, 1889. It was reportedly not his first time experiencing a vision directly from God; but as a young adult, he claimed that he was then better equipped, spiritually, to handle this message. Jack had received training from an experienced holy man under his parents' guidance after they realized that he was having difficulty interpreting his previous visions. Jack was also training to be a "weather doctor", following in his father's footsteps. He was known throughout Mason Valley as a gifted and blessed young leader. Preaching a message of universal love, he often presided over circle dances, which symbolized the sun's heavenly path across the sky.

Anthropologist James Mooney conducted an interview with Wilson prior to 1892. Mooney confirmed that his message matched that given to his fellow aboriginal Americans. This study compared letters between tribes. Wilson said he stood before God in heaven and had seen many of his ancestors engaged in their favorite pastimes. God showed Wilson a beautiful land filled with wild game and instructed him to return home to tell his people that they must love each other, not fight, and live in peace with the whites. God also stated that the people must work, not steal or lie, and that they must not engage in the old practices of war or the traditional self-mutilation practices connected with mourning the dead. God said that if his people abided by these rules, they would be united with their friends and family in the other world.

In God's presence, there would be no sickness, disease, or old age. Wilson was given the Ghost Dance and commanded to take it back to his people. He preached that if the five-day dance was performed in the proper intervals, the performers would secure their happiness and hasten the reunion of the living and deceased. Wilson said that God gave him powers over the weather and that he would be the deputy in charge of affairs in the western United States, leaving current President Harrison as God's deputy in the East. Jack claims that he was then told to return home and preach God's message.[2]

Jack Wilson claimed to have left the presence of God convinced that if every Indian in the West danced the new dance to "hasten the event", all evil in the world would be swept away, leaving a renewed Earth filled with food, love, and faith. Quickly accepted by his Paiute brethren, the new religion was termed "Dance In A Circle". Because the first European contact with the practice came by way of the Sioux, their expression Spirit Dance was adopted as a descriptive title for all such practices. This was subsequently translated as "Ghost Dance".

Spread of the prophet's message

Through Native Americans and some Anglo-Americans, Wilson's message spread across much of the western portion of the United States. Early in the religious movement, many tribes sent members to investigate the self-proclaimed prophet, while other communities sent delegates only to be cordial. Regardless of their initial motivations, many left as believers and returned to their homeland preaching his message. The Ghost Dance was also investigated by many Mormons from Utah, for whom the concepts of the Native American prophet were familiar and often accepted.While most followers of the Ghost Dance understood Wovoka's role as being that of a teacher of pacifism and peace, others did not.

An elaboration of the Ghost Dance concept was the development of Ghost Shirts, which were special garments which warriors could wear. They were rumored to repel bullets through spiritual power. It is uncertain where this belief originated. James Mooney argued that the most likely source is the Mormon temple garment (which Mormons believe protect the pious wearer from evil). Scholars believe that in 1890 chief Kicking Bear introduced the concept to his people, the Lakota Sioux.

The Lakota interpretation drew from their traditional idea of a "renewed Earth" in which "all evil is washed away". This Lakota interpretation included the removal of all Anglo-Americans from their lands. In contrast, Wilson's version encouraged harmonious co-existence with European Americans.

Political influence

In February 1890, the United States government broke a Lakota treaty by adjusting the Great Sioux Reservation of South Dakota (an area that formerly encompassed the majority of the state) and breaking it up into five smaller reservations.The government was accommodating white homesteaders from the eastern United States; in addition, it intended to "break up tribal relationships" and "conform Indians to the white man's ways, peaceably if they will, or forcibly if they must." On the reduced reservations, the government allocated family units on 320-acre (1.3 km2) plots for individual households. The Lakota were expected to farm and raise livestock, and to send their children to boarding schools. With the goal of assimilation, the schools taught English and Christianity, as well as European-American cultural practices. Generally, they forbade inclusion of Native American traditional culture and language.

To help support the Sioux during the period of transition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) was to supplement the Sioux with food and to hire white farmers as teachers for the people. The farming plan failed to take into account the difficulty which Sioux farmers would have in trying to cultivate crops in the semi-arid region of South Dakota. By the end of the 1890 growing season, a time of intense heat and low rainfall, it was clear that the land was unable to produce substantial agricultural yields. Unfortunately, this was also the time when the government's patience with supporting the so-called "lazy Indians" ran out. They cut rations for the Sioux in half. With the bison having been virtually eradicated a few years earlier, the Sioux were at risk of starvation.

The people turned to the Ghost Dance ritual, which frightened the supervising agents of the BIA. Kicking Bear was forced to leave Standing Rock, but when the dances continued unabated, Agent McLaughlin asked for more troops. He claimed theHunkpapa spiritual leader Sitting Bull was the real leader of the movement. A former agent, Valentine McGillycuddy, saw nothing extraordinary in the dances and ridiculed the panic that seemed to have overcome the agencies, saying: "The coming of the troops has frightened the Indians. If the Seventh-Day Adventists prepare the ascension robes for the Second Coming of the Savior, the United States Army is not put in motion to prevent them. Why should not the Indians have the same privilege? If the troops remain, trouble is sure to come."

Nonetheless, thousands of additional U.S. Army troops were deployed to the reservation. On December 15, 1890, Sitting Bull was arrested for failing to stop his people from practicing the Ghost Dance. During the incident, one of Sitting Bull's men, Catch the Bear, fired at Lieutenant "Bull Head," striking his right side. He instantly wheeled and shot Sitting Bull, hitting him in the left side, between the tenth and eleventh ribs; this exchange resulted in deaths on both sides, including that of Sitting Bull.

Wounded Knee

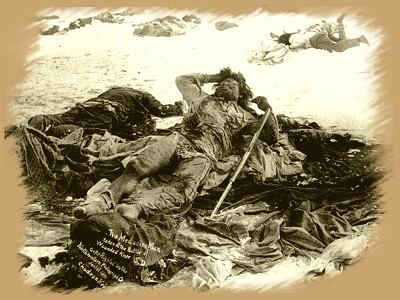

Spotted Elk (Lakota: Unpan Glešká – also known as Big Foot), was a Miniconjou leader on the U.S. Army's list of 'trouble-making' Indians. He was stopped whilst en route to convene with the remaining Sioux chiefs. U.S. Army officers forced him to relocate with his people to a small camp close to the Pine Ridge Agency. Here the soldiers could more closely watch the old chief. That evening, December 28, the small band of Sioux erected their tipis on the banks of Wounded Knee Creek. The following day, during an attempt by the officers to collect weapons from the band, one young, deaf Sioux warrior refused to relinquish his arms. A struggle followed in which somebody's weapon discharged into the air. One U.S. officer gave the command to open fire, and the Sioux responded by taking up previously confiscated weapons; the U.S. forces responded with carbine firearms and several rapid-fire light-artillery (Hotchkiss) guns mounted on the overlooking hill. When the fighting had concluded, 25 U.S. soldiers lay dead, many killed by friendly fire. Amongst the 153 dead Sioux, most were women and children. Following the massacre, chief Kicking Bear officially surrendered his weapon to General Nelson A. Miles.

la ghost dance

La Ghost Dance (en français la Danse Des Esprits) était un mouvement religieux nord-amérindien. Sa pratique la plus connue était une danse menée en cercle.

Origines du mouvement

En 1890, Jack Wilson, un chef religieux améridien connu sous le nom de Wovoka (« faiseur de pluie »), déclara que pendant l'éclipse totale du soleil du 1er janvier 1889 il lui avait été révélé qu'il serait le Messie de son peuple. Il donna sa première Danse Des Esprits quelque temps après cette vision dans le but de contacter de nouveau les esprits par la transe1. Le mouvement spirituel qu'il créa fut appelé « danse des esprits » par les Blancs. Il s'agit d'un mélange syncrétique de spiritualismePaiute et de christianisme Shaker. Les danses avaient pour objectif de favoriser l'arrivée d'un sauveur de la cause amérindienne1.

Bien que Wilson ait prêché que des tremblements de terre seraient envoyés pour tuer tous les Blancs, il a également enseigné que jusqu'au jour du Jugement dernier, les Amérindiens devaient vivre en paix et ne pas refuser de travailler pour les Blancs.

Wounded Knee

Les deux premiers convertis furent les guerriers Lakota de la réserve indienne de Pine Ridge, Kicking Bear et Short Bull. Tous les deux ont reconnu que Wilson avait fait de la lévitation devant eux, mais ils ont interprété ses paroles différemment. Ils ont rejeté la prétention de Wilson d'être le Messie et ont cru que le Messie n'arriverait pas avant 1891. Ils ont aussi refusé le pacifisme de Wilson et estimé que des vêtements spéciaux, les "chemises fantômes" ("ghost shirts") les protégeraient des balles.

La majorité des Indiens de la réserve de Pine Ridge avait sans doute été convertie, mais le chef Sitting Bull n'en faisait pas partie. Cependant, il garantit la liberté religieuse ; les fonctionnaires fédéraux interprétèrent néanmoins cette tolérance comme un appui total et le Général Nelson Miles ordonna l'arrestation de Sitting Bull. 43 policiers indiens essayèrent de l'arrêter le 15 décembre 1890 à la "Standing Rock Agency". Pour des raisons peu claires, une fusillade s'ensuivit et Sitting Bull était parmi les douze tués.

Quatre cents danseurs des esprits Hunkpapa Lakota s'enfuirent à la réserve indienne de Cheyenne River des Lakota Minniconjou. La majorité fut convaincue de se rendre, mais 38 continuèrent de résister sur le site du campement de Big Foot, demi-frère de Sitting Bull, qui avait été choisi comme nouveau chef. Miles ordonna aussitôt l'arrestation de Big Foot mais l'armée temporisa, espérant que sa réputation pacifiste empêcherait les hostilités. Quand les Hunkpapa arrivèrent, apeuré par l'arrivée de nombreux soldats en réaction aux danseurs des esprits, le peuple insista pour qu'il accepte une invitation du chef Red Cloud (qui ne faisait pas partie du mouvement de la Danse des esprits) à la "Pine Ridge Agency" pour l'aider à faire la paix avec les Blancs. 350 Lakota au total essayèrent de rejoindre Pine Ridge.

Les danseurs des esprits avaient déjà été affaiblis par le retrait volontaire de la plupart des Oglala et des Brulé « hostiles » du bastion des danseurs des esprits. Craignant que la destination de Big Foot ne soit le bastion et que sa présence ne rallume la crise, Milles déploya le 6e et le 9e régiment de cavalerie pour bloquer les Minniconjou.

Le clan de Big Foot fut intercepté par le Major Samuel Whitside et environ 200 hommes du 7ème régiment de cavalerie. Whitside transfera Big Foot vers une ambulance de campagne en raison d'une grave pneumonie et escorta les Lakota à leur camp pour la nuit à Wounded Knee Creek. L'armée fournit aux Lakota des tentes et des rations et détermina qu'il y avait alors 120 hommes et 230 femmes et enfants.

Le matin suivant, les Lakota trouvèrent en face d'eux le reste du régiment, avec son commandant, le colonel James W. Forsyth, arrivé pendant la nuit, ainsi qu'une batterie de mitrailleuses Hotchkiss du 1er régiment d'artillerie. Les armes étaient disposées sur une petite colline surplombant le campement. Forsyth informa son commandant que les Lakota devaient être transférés dans un camp militaire à Omaha dans le Nebraska.

"Il commencèrent à confisquer les armes aux indiens. Lorsqu'un coup de feu partit accidentellement, les soldats ouvrirent le feu, et en quelques minutes, tuèrent plus de 370 lakotas. Puis ils poursuivirent les femmes et les enfants, pour les abattre à plusieurs kilomètres du lieu de la confrontation première."

Caractéristiques

Avant de danser, les participants devaient se purifier et la consommation d'alcool était prohibée. Les danses s'étalaient sur trois ou quatre jours et on dansait toute la journée sans s'arrêter pour suivre la course du soleil Elles étaient accompagnées uniquement de chants. À la fin du XIXe siècle, le Bureau des affaires indiennes interdisait les pratiques religieuses de la Ghost Dance Aujourd'hui, la danse des Esprits est un élément du renouveau amérindien aux Etats-Unis et connaît un certain succès dans les tribus du sud du pays Elle permet de commémorer le massacre de Wounded Knee.

A découvrir aussi

- Lewis and Clark - Early explorers of the West

- CAHOKIA MOUNDS

- histoire des premiers amerindien jusqu'a 1766

Inscrivez-vous au site

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 76 autres membres